Q: So. What seems to be the problem?

A: There are 19 million adoptable orphans, and there's catastrophic climate change on the horizon. Contributing a child to the world both makes climate change worse and, if we don't get our act together, it might actually not be all that great for the child either.

You have two tracks. You could say climate change is a big structural problem, so it requires a structural solution; that's a policy question. Or you could say a problem like climate change requires that we change our culture of individual obligation, and everybody needs to think about having small families.

Q: That seems like a pretty heavy ask. People don't even want to think about having small bags of movie popcorn.

A: Well, the argument goes like this: Okay, humans have shown me that they're just not willing to give up their toys. And so we need another option on the table. You want to continue to live in your 10,000-square-foot house? You know, fly private jets around, and that kind of thing? Well, that would mean a lot fewer people on the Earth.

Source: Amazon.com

Q: At least in the carbon-heavy countries? Do you think that would actually ever happen?

A: Mostly I want to put it on the table. Population is a central part of the equation for total emissions, but that gets kind of looked over because people don't like to talk about it.

Total emissions is per-capita emissions times population, minus technological advances. We've been trying to get you to give up your toys—to change per-capita emissions. So if you're really going to continue to show reluctance, well, here's the other option: We'll start putting pressure on families. If that pressure's really, really, really undesirable, then, well, maybe people decide to start doing the other thing.

If we could fix everything through decarbonizing our economy, then it's likely that the population variable wouldn't be a real concern.

Q: It does have the distinct unpleasant feel of a moral gun to the head.

A: Here's my actual suspicion, though: Most people don't find it that undesirable. Demographic trends the world over show when you give women choice, you educate them, you give them power in the household, and you start to fight back against patriarchal society, then fertility rates go down.

Q: People are helpful to have around, though, if you want to have an economy. China may learn that the hard way.

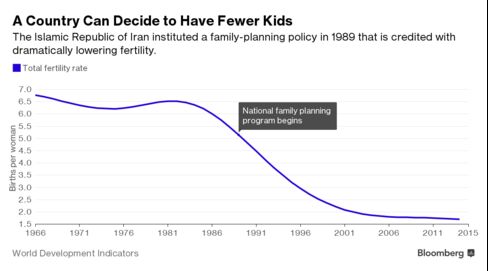

A: This is the most infamous example, but it turns out there's been a lot of countries with pretty influential fertility-reducing policies and strategies. What we found is that some of them are really, really good. That's one of the reasons people balk at this sort of argument. They say, 'Look what happened in China.' None of those are arguments against any kind of strategies; those are arguments against the ways the Chinese government employed them.

We put policies on a kind of spectrum of invasiveness, what we call a

coercion spectrum. There are things we obviously should never do. You should never violate basic human rights by forced sterilization or forced abortion. That's off the table. We're not going to talk about that. Nobody's going to talk about that.

But this is actually really good fertility policy: Provide family planning. Provide your people with health care. Educate women, and empower women within the home.

There have been media policies, poster campaigns. Some of them are a little nasty, showing lots and lots of poor people reaching through gates and saying, 'Don't have too many kids, we don't have enough jobs.' And stuff like that. That feels a little nasty. Some of them are just, like, happy pictures of a couple with one child saying, 'Please stop at one.' A lot of these media campaigns had verifiable success. Data was collected and fertility rates dropped.

Q: Pope Francis wants to fight climate change, but I'm not sure he'd be down with your full argument here.

Close all those tabs. Open this email.

Get Bloomberg's daily newsletter.

A: Religion—not only Catholicism but Mormonism, ultra-orthodox Judaism, that sort of thing—probably is a really good reason to think about using population as a way to raise the stakes. If you're Catholic, and you're really going to stare climate change in the face, refuse contraception, and continue to have sex anyway, there's the foreseeable outcome that you will have more children than average. Well, then you really better be doing your darnedest in all sorts of other ways. When you make that choice, there's a cost. You have to pay for it in some way.

Q: How's the reception to this work been?

A: The far-right hate machine is in full swing, and I'm getting hate mail. All that good stuff.