Paul Drake

Well-Known Member

RIP Meatloaf

www.upi.com

www.upi.com

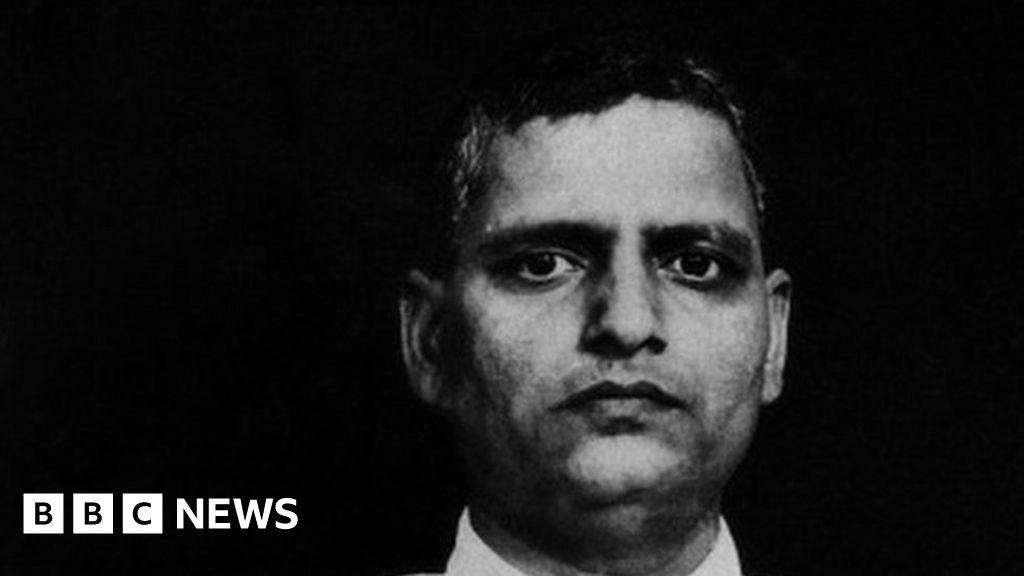

I saw that he died but didn't recognize the name. I hadn't watched "WKRP in Cincinnati"RIP Dr. Johnny Fever. Howard Hesseman.